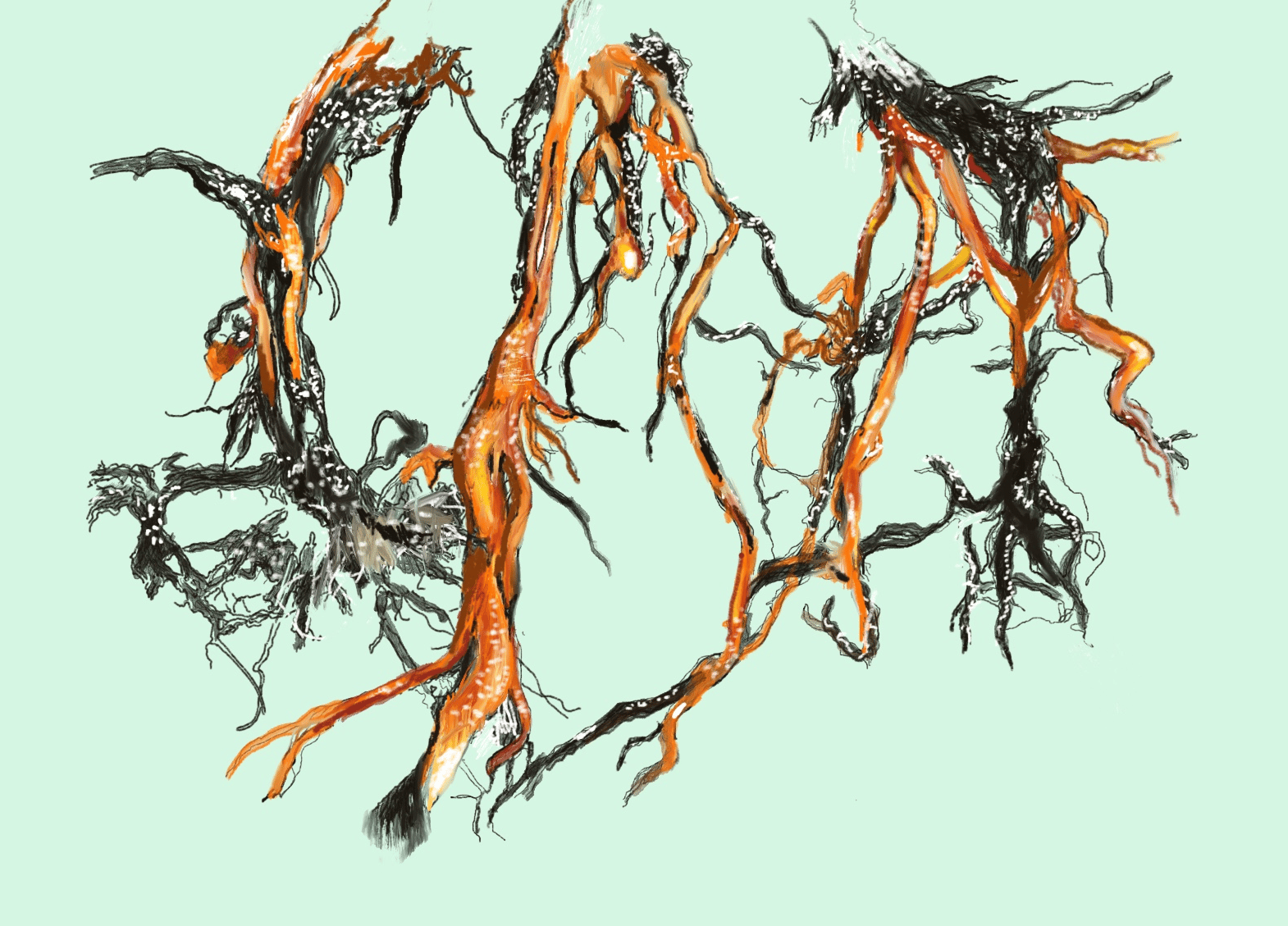

Illustration: Caroline Villard

THIS SERIES STARTED WITH A QUESTION. Why can’t Manchester United, one of the world’s biggest sporting institutions, reliably put out a team that inspires and delights its fans?

I had a hunch it was an example of what I call corporate rot — the sclerosis, disconnection, risk-aversion and obsession with numbers that paralyzes organizations when they reach a certain scale.

It’s a phenomenon that colors our lives a lot more than it used to. What David Graeber called bullshit jobs are the norm now. We all have to set aside hours a week to enter high-stakes bureaucratic hells and hear the word ‘policy’ over and over (from someone who has their own bullshit job). It feels like being on a long flight. Anxious, dehumanised and powerless, with a film of mouth plaque.

We’re taught to see it as petty. Beneath us. A waste of time to get upset about. But to me the wave of resentment and bitterness and frustration that has swept through Western politics in recent years is partly a search for places to put that feeling.

Certainly, many issues we see as political are the result of corporate policies and practices superseding the law as the operating system for societies. (Free speech is dictated more by Meta, Alphabet, TikTok and Apple than any government.)

A sports team seemed like a good way to examine the problem. Because it is what it is. There’s no debate. It’s either thrilling people, and winning games, or it is not. So I contacted everyone I could think of who might know about the reality of life inside Manchester United — two dozen current and former executives, coaches, players and others.

Only two would talk to me, because Manchester United has a lot of money, and none of them wanted to displease it in case it wanted to give them some of it. They were a former Premier League player and manager, and an executive who worked closely with the Glazer family, the majority owners of the club.

The executive said that the Glazer family suffers for its size. There are six siblings, and the complexities of their internal dynamics trickle down. Most of the family just want a great team. Some want to “win the game of sports team ownership as a capitalist exercise”. Even when the very best intentions make it through, they’re filtered via so many layers of people who just want to please the boss that they land strangely, and miss the mood of fans and players. The result is a muddle of great initiatives that nobody notices, and financial maneuvering which everyone obsesses over.

I asked the former player and manager about the club's record of taking players and managers who had excelled, and turning them to mediocrity. Why, if others have seen what happened to Jadon Sancho or Antony or Ruben Amorim, do they continue to say yes when the club comes calling?

He told me that those who work on the front lines of the sport don’t have the luxury of wondering whether the running of the institution will help or hurt them. “It's a short career. You go where you're wanted,” he said. It doesn't hurt that Manchester United pay better than most.

He said that what he saw was a disconnect between the layers of the hierarchy. A well-run club is flat — owners and executives, managers and coaches, players and everyone else are aligned and in regular contact. They want the same thing, and they're all working towards it. Badly-run clubs lack that unity of purpose.

Please consider upgrading, so we can tell even more weird, wonderful and heartfelt stories in 2026

I got stuck on the word purpose. And then I came across a management theory by the British theorist Stafford Beer whose title alone unlocked the mystery: The purpose of a system is what it does.

“It stands for bald fact,” he said, “which makes a better starting point in seeking understanding than the familiar attributions of good intention, prejudices about expectations, moral judgement, or sheer ignorance of circumstances.”

There is no point, he said, “in claiming that the purpose of a system is to do what it constantly fails to do”. In 2018, the then-manager of Manchester United, Jose Mourinho, cited a similar concept from the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in a press conference: “the truth is in the whole”.

What does Manchester United do? Makes money and serves its fans the least it can without having them leave. The purpose of a system is what it does. What do many corporations do? Make money and serve their customers the least they can without having them leave. The purpose of a system is what it does.

The frustration is not an accident. It’s a feature. To provide more, to seek joy or wonder or thrill or kindness, is to mis-serve your shareholders.

To me it’s perversely hopeful. It says that we can leave aside the conspiracy theories, cease to apply our judgements, accept that we don't know what it’s like for even the best people inside these systems, and strive to make better ones ourselves.

But it does demand we understand what is happening, so we can start new and better things, or stave off rot before it sets in.

We’ll start by going deep into the company that set the intentions and tone for the corporate world more than any other: the management consultancy McKinsey.

We have an insider account that leaves aside the distracting controversies to look at what it does every day, and how that affects you, including why every drive from an American airport into town looks the same.

It is followed by an account of what happens when McKinsey-ism is applied to one of the largest organisations on earth — Britain's National Health Service.

The intention of the series was to reveal an injustice, and give us all a way to talk about this nebulous phenomenon. What the stories actually did was make me laugh, and make my interactions with big organizations easier. I can live with that purpose. ⸭

RAVI SOMAIYA is the founder of Bungalow. You can email him here.