Illustration: Caroline Villard

THE TOWN OF BLANKENBURG SITS AT THE NORTH FOOT OF THE HARZ, a mystical highland region of mountains, castles, caves and eerie, straight pine trees on sandy, dry soil, that is the epicenter of German fairytale myth.

A few hundred meters east of the old town is one end of the Teufelsmauer, or the Devil’s Walls, a long row of stone cliffs that are reputed to have been built by Satan to divide his part of the world from God's, or by giants descended from the Biblical Cain, perhaps as altars of sacrifice.

Another folk tale, recorded in the 19th century, tells of four working men in Harz who were mowing grass. One among them was a werewolf. A traveling merchant stopped to let his livestock graze nearby. Three of the men stopped work. But the fourth, the lycanthrope, unable to resist the delicious horses he saw arrayed, slipped away and transformed. When his colleagues confronted him, he ran into the woods in wolf form, never to be seen again.

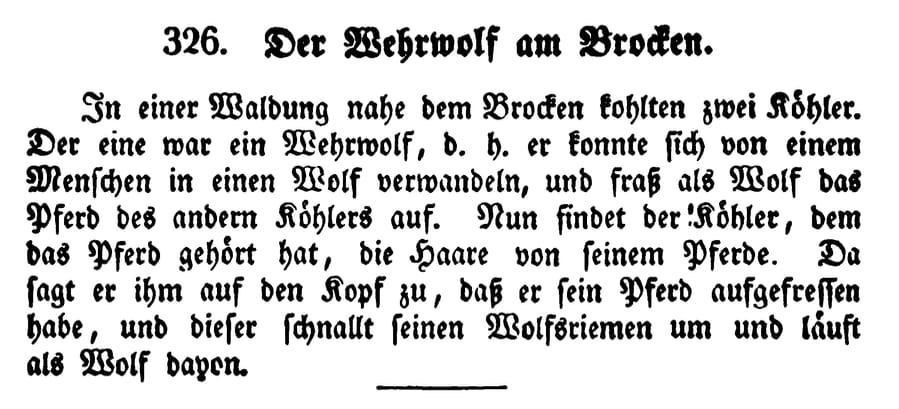

An excerpt from Heinrich Pröhle’s Harzsagen, 1859 (University of California)

Underneath the 2,000-acre forest north of town, known as the Heers, is an eight-kilometre network of tunnels driven into the sandstone rock in 1944 by prisoners from a local subcamp of the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp. During the war it was intended to house a facility for making V-2 rockets. It is now home to what’s said to be the world's largest underground pharmacy, operated by the German armed forces.

The woods were only planted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but ghostly pale sandcaves in the area have attracted ritual gatherings and inspired myths since the times of the pre-Christian Germanic tribes. In recent years, the small volunteer fire department responsible for the Heers has grappled with a new local curiosity.

Blankenburg as depicted in Johann Georg Leuckfeld's Antiquitates Blanckenburgens, 1708 (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek)

About seven years ago, unexpected calls started coming in. They alerted officials to a mysterious man in the forest. Signs of habitation were found. So were the remains of fires, abandoned and poorly extinguished. Someone wearing a costume, or animal skin, perhaps a wolf pelt. Someone living secretly in the forest.

Reports involving fire were taken especially seriously. Even a fire that seems like it is out can burn on undetected, and reignite into the pines. And other men are known to live in the forests of Germany, as wild as they can manage. But the calls led to nothing, except frustrated firemen.

On March 25, 2023 at 10:31.a.m., another call came in. This time it was more explicit. There was a Wolfsmensch — a wolfman — in the Heers. A thin column of smoke could be seen rising above the woods to mark his location.

Nine firefighters, two engines and two police patrol cars traveled to the heart of the forest. Alexander Beck, the local fire chief, found the illegal fire,. He looked up at the horizon, and saw a man fleeing into the woods, possibly wearing a fur cap. Later, officials found temporary dwellings made of branches, sometimes expertly constructed.

“Someone there knows a thing or two about living outdoors and adapts to the changing seasons," the fire chief told the broadsheet Volksstimme. Ultimately, he didn’t think all the reported incidents related to the wolfman figure, or that the wolfman lived permanently outdoors.

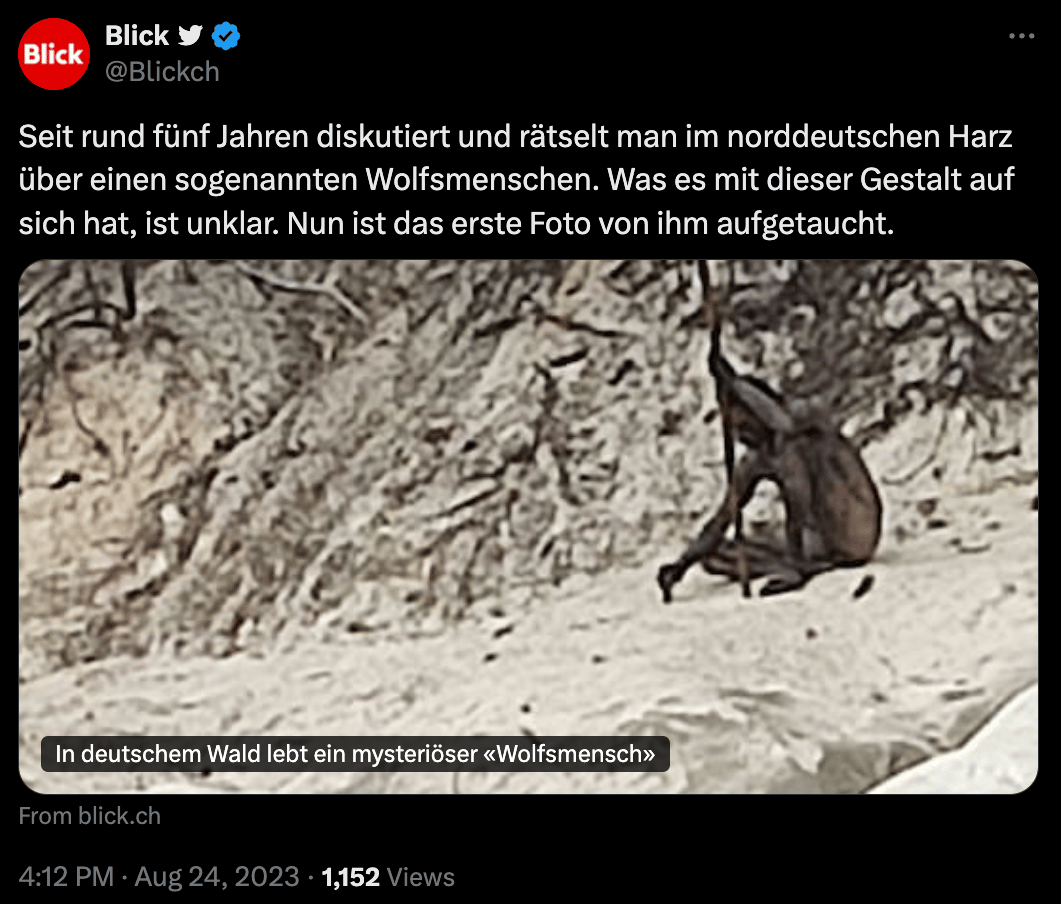

Then, on August 22, 2023, at about 6.30pm, a visitor named Gina Weiss and her partner Tobi were walking nearby, at the sandstone caves which form the epicenter for ritual activity. Something caught their attention, about 50 feet away, on top of the caves. It looked like a man, but not wearing clothing. Smeared in dirt, perhaps, and holding a long stick, which he was using to scratch into the ground.

"He didn't take his eyes off us, didn't say a word," she told Bild, Germany’s largest tabloid, which published the image. "He looked dirty and acted like a caveman from a history book." She took a grainy picture with her phone. It was picked up by the international media.

A tweet by Swiss news publication Blick containing the image of the Wolfsmensch first published by Bild

Soon the forest was filled with reporters, and motion or heat-triggered wildlife cameras, with night vision. They caught nothing.

Then, on the afternoon of December 22, 2024, the fire service received another call. A column of smoke rising from a different area, this one west of town.

Thirteen firefighters and three engines were dispatched. Police arrived after they had extinguished the flames. After investigating the scene, officers determined a makeshift wood shelter caught fire, which spread into nearby vegetation. It was too near a walking path to be the work of someone trying to hide, officials reasoned. Maybe it was an improvised site for illegal waste burning, they thought.

The only way to find out what happened next seemed to be to venture into the forest myself.

This is a free preview of the fourth story in Bungalow’s first series, Myths and Legends. If you like it, subscribe here for more.

Blankenburg. Early morning, November 20, 2025. I planned to arrive at the sand caves before sunrise, and survey the area and the woods, leaning on knowledge gleaned from years served as a search and rescue responder in eastern Maine.

It felt more like tourism than any kind of quest. Google maps told me the caves were an hour away, so I threw on a trench coat and some sneakers and headed out. I was guided north of the city along paved roads and sidewalks, and eventually connected with a dirt path on the other side of a highway overpass.

The Heers stood tall where the path followed. When it forked at the edge of the woods, I turned east. I began to ascend, ever so slightly, as it started to rain. Then I reached a barbed wire-topped fence. The military base, gray and misty and empty, except for warning signs. I couldn't cross it, so I redirected.

The fence line of the Bundeswehr’s Versorgungs- und Instandsetzungszentrum Sanitätsmaterial Blankenburg facility (Bungalow)

Then the woods attacked. I was pushed upwards, to the north, the direction of the sand caves. I found myself first at the top of a steep cliff, far above the path I was aiming for. I walked along it, until I hit another fenceline for the base, and pushed upwards again, rainsoaked and exhausted and sore from falling where my sneakers declined to grip the slick ground.

When I emerged from the treeline it became clear I'd accidentally climbed a mountain. The Heers and the sandcaves where the wolfman was spotted were immediately east of me.

Nearby was Burg Regenstein, the site of a medieval rock castle set atop elevated stone cliffs. The castle was the seat of the Counts of Regenstein, until it fell into disrepair. One tale says that a ghostly wagon, pulled by eight horses, can sometimes be seen driving around the pathways to the castle before vanishing.

I could see, from my accidental elevation, that there were no fires lit, no smoke rising from pits where a wild man might be. I made it to the bottom and, finally, the Heers itself. It's not hard to see how this place gave rise to so many myths and legends. And how those myths and legends sometimes bled into real-life horror.

Twelve miles away is the highest peak in the Harz, the Brocken. Witches are said to gather there every year, a ritual alluded to by Goethe in Faust.

Witch trials, which resulted in tens of thousands of prosecutions, were not uncommon in this region in the 16th and 17th centuries and in some cases dealt with allegations of lycanthropy.

An image from a 1555 witch hunt broadsheet which described the burning of women in Derenburg, not far from Blankenburg in the County of Regenstein (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek)

Germany’s most famous werewolf case occurred in 1589 when Peter Stump, a widowed farmer, was tortured into confessions of witchcraft, serial murder, and making a deal with the Devil for his shapeshifting ability.

A 1589 anti-witchcraft leaflet illustrates the torture and execution of alleged werewolf Peter Stump (Hessisches Landesarchiv)

He was brutally executed along with his daughter and alleged mistress, both accused accomplices. As a warning, authorities placed his severed head on a pole next to the figure of a wolf.

After two hours of searching the trails through the forest, I do not find the wolfman or any sign of him. No firepits, no obvious shelters. Four more days of trail searches — including one of the other forest where the charred shelter was found last December — yield nothing.

But at the sand caves, where the man was photographed, there are strange footprints. Impressions of both human and canine feet intersperse. In some places, large paws appear to take the next step after a shoe.

Footprints in the sand by the caves show signs of man and canine (Bungalow)

I am aware it's almost certainly hikers, and their dogs. But in a moment when the world has returned to some of the mob superstition, and violent suppression, of ancient Harz, it feels like a sign that perhaps, in the trees around me, watchful and at one with the woods, is a man who simply does not want to be found. ⸭

This is a free preview of the fourth story in Bungalow’s first series, Myths and Legends. If you liked it, subscribe here for more.

SEAN CRAIG is a Berlin-based journalist. He has contributed to The Guardian, Pitchfork, The Daily Beast and the Financial Post.