Illustration: Caroline Villard

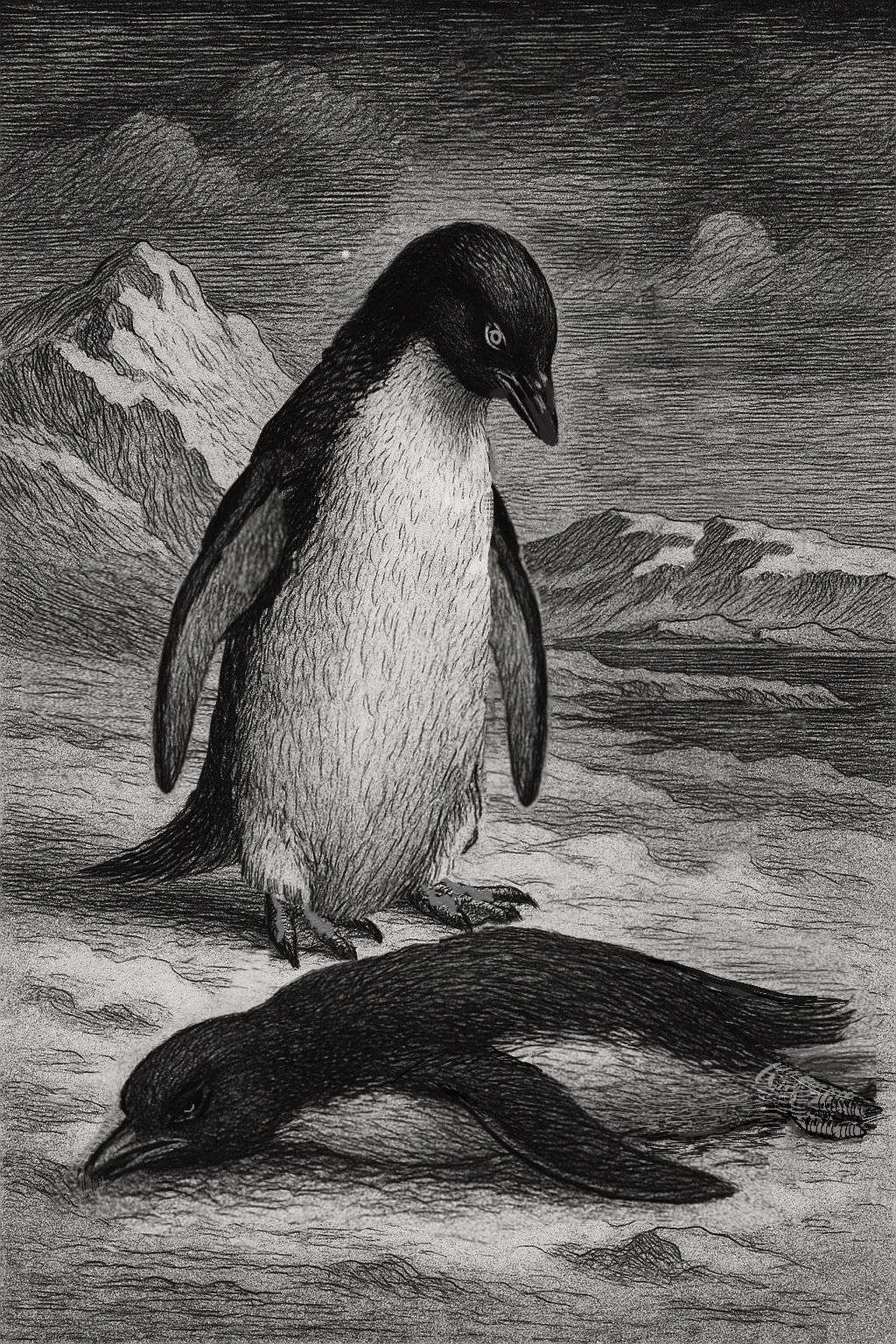

EVERY GENERATION HAS ITS ROMANTIC MYTHS. OURS IS ABOUT PENGUINS. You will have heard it if you have watched enough romance-based reality TV.

Penguins mate for life, the story goes. At the beginning of the courtship, the male penguin seeks out a perfect rock on a frigid Antarctic beach. He carries it painstakingly in his mouth, and presents it to the female who has captured his heart. If she accepts it, they are effectively betrothed, and will raise their annual brood together. United against life.

I wondered if this was true, so I decided to report it out. The first answer I got was that, yes, it seems to be, in a way, for specifically Adélie penguins, the most widespread variant. (I'd describe them as classic penguins.) The male penguin absolutely does bring rocks to the female, and they do form long-term monogamous relationships.

Illustration: Caroline Villard

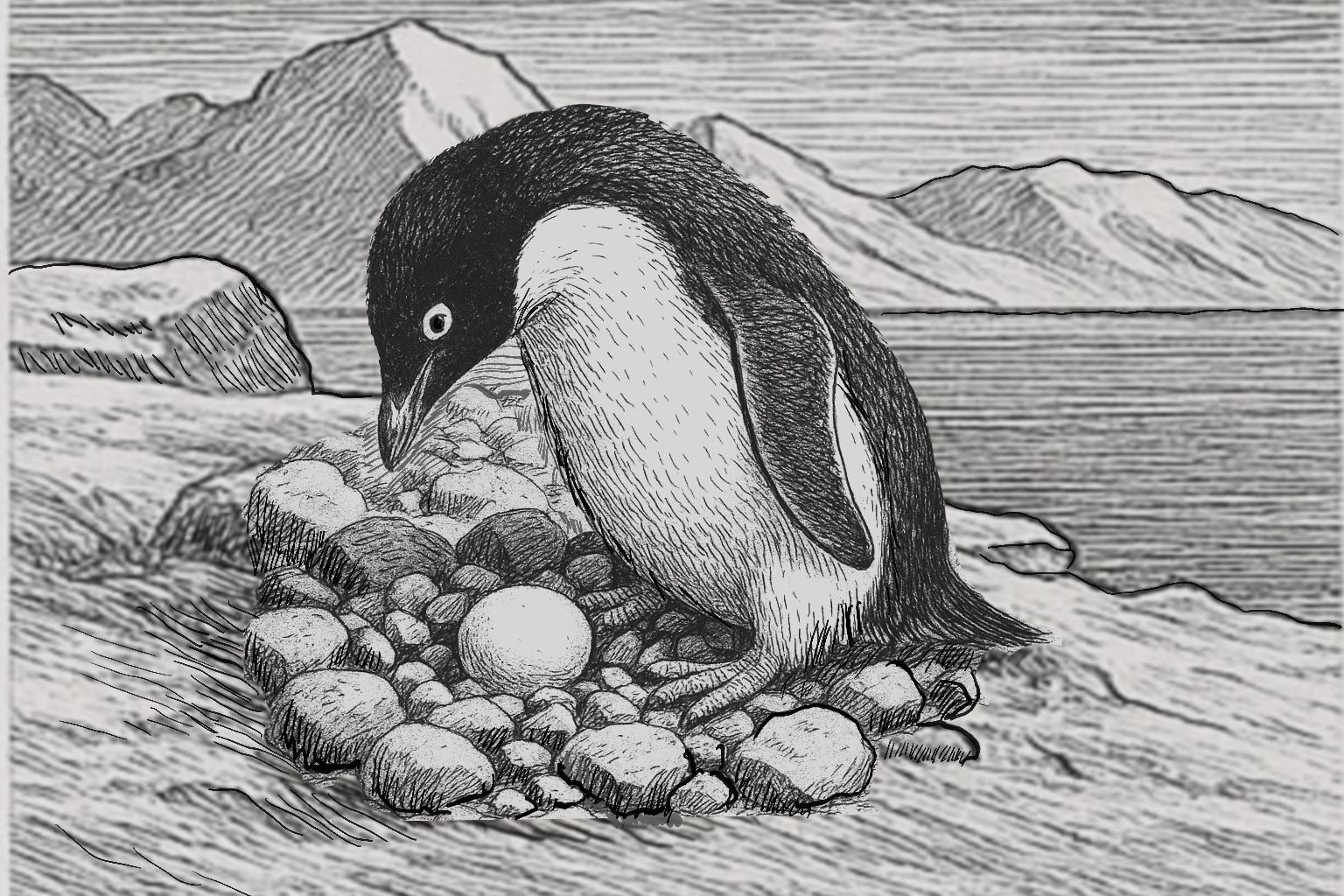

There's more detail. The Antarctic, as you might imagine, is cold and wet. It's deadly to eggs that need to be kept warm and dry. So penguins build nests that are little hills of rocks with a lined dip in them. This raises the eggs above the ground so they will not be damaged by snow-melt or other water.

What we interpret as a sacred rock or an avian wedding ring may just be the male presenting material for nest-building. Showing he's a responsible father. That sounded like the sort of messy complexity and pragmatic romance that often marks reality, so I felt satisfied and smug that it was the truth.

I was wrong. It was only the very surface of a tale so graphic and unsettling that it was first written only in code, and then suppressed by the British for more than a century.

Illustration: Caroline Villard

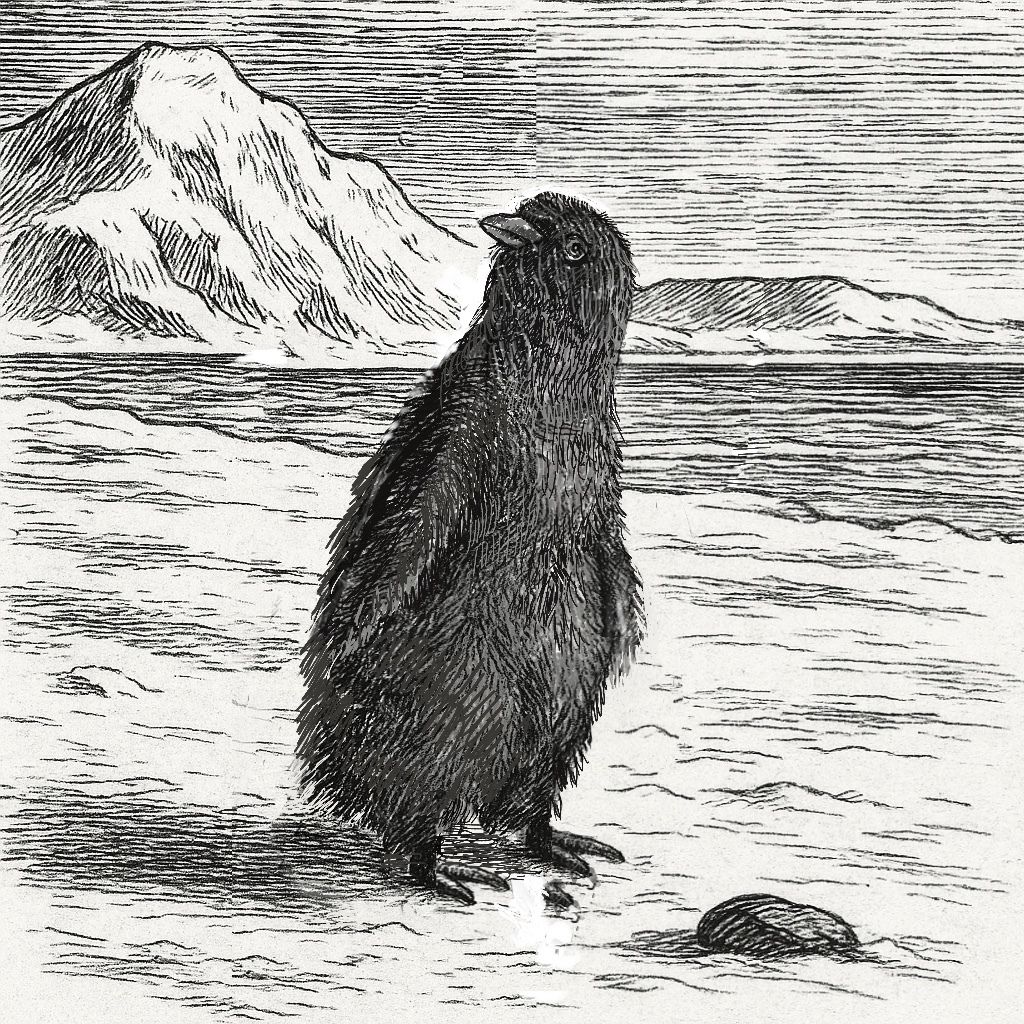

It begins with Robert Scott's doomed Antarctic expedition of 1910. Among the 65 people on that deadly journey was a surgeon and zoologist called George Murray Levick. Levick and the members of his group — five experts in surveying, magnetic observation, geology, microbiology and meteorology, and survival — were forced to change their plans. They were stranded away from the main expedition, and spent winter on a frozen pile of jagged black basalt called Inexpressible Island.

They covered themselves in rancid-smelling blubber to stay warm and ate the equally rancid-tasting blubber to survive. They did not consider their separation from the death and desolation that befell Scott and the others to be the stroke of good fortune that history would suggest. “The road to hell,” Levick noted, “might be paved with good intentions, but it seemed probable that hell itself would be paved something after the style of Inexpressible Island.”

It did give Levick the opportunity to do something that nobody has since done. He spent an entire breeding cycle, nearly a year from February 1911 onwards, observing the world's largest colony of Adelie penguins, on nearby Cape Adare.

Illustration: Caroline Villard

The book that resulted, Antarctic Penguins, along with nine penguin skins, his notes and photographs, added a vast quantity of basically irreplaceable context and detail that still comes in useful for calculating the effects of climate change on penguins. (It also shamelessly anthropomorphised. One reviewer described it as an account of “strange, erect, man-like little birds”.)

On page 97 there was one intriguing aside. It was about what he called ‘hooligan cocks’ — unattached males, who never had a mate, or whose mate had died.

Illustration: Caroline Villard

“Many of the colonies,” he wrote, “especially those nearer the water, are plagued by little knots of ‘hooligans’ who hang about their outskirts, and should a chick go astray it stands a good chance of losing its life at their hands. The crimes which they commit are such as to find no place in this book, but it is interesting indeed to note that, when nature intends them to find employment, these birds, like men, degenerate in idleness.”

Levick had, in fact, closely observed these hooligan cocks. But he was so shocked by what he saw that he wrote his notes on them in the Greek alphabet, as a rudimentary kind of code. When he submitted his book to the Natural History Museum, they removed the resulting chapter — entitled “Sexual Habits of the Adélie Penguin” — entirely.

Illustration: Caroline Villard

It was deemed too horrifying and frankly too revealing of uncomfortable facets of nature. They printed only a few copies for research use, marked “Not for publication”. They got their wish for nearly a century, until one copy emerged, and finally revealed what had so scandalized Levick and the museum's grandees.

The chapter focused on the rookery, a vast landscape of female penguins embedded in the raised, rocky craters of their nests. Underneath each were eggs. And around them, other penguins were fervently trying to attain their happy state of gestation.

Illustration: Caroline Villard

Sex was in the air and young males in particular were so intoxicated, wrote Levick, that their “passions seemed to have passed beyond their control”. Some wandered around fucking the clear Antarctic air, to hollow and sticky completion on the rocky ground. And that, Levick writes “was the least depraved of the acts which we saw”.

The dead body of a penguin, he said, can last for years well-preserved by the cold. So generations of penguin corpses were strewn about the rookery. Males had sex with the bodies, with every sign of satisfaction. And as the season went on, and the number of unattached males increased (through predation of their partners, or accidental deaths), they grew more desperate, Levick wrote. He described one particularly savage incident.

Illustration: Caroline Villard

“I have said that cramp or some sort of paralysis occasionally attacks the penguins after they have been in the sea.

One day I was watching a hen painfully dragging herself across the rookery on her belly, using her flippers for propulsion as her legs trailed uselessly behind her.

As I was just wondering whether I ought to kill her or not, a cock, seeing her pass, ran out from the outskirts of a neighbouring knoll and went up to her. After a short inspection he deliberately copulated with her, she being, of course, quite unable to resist him.

He had hardly left her before another cock ran up, and, without any hesitation, tried to mount her. He fell off at first, and then, desisting, stole two stones from neighbouring nests, dropped them one after the other in front of her, after which he mounted and performed the sexual act.”

Five more males either did the same, or tried. And they also sought out vulnerable chicks for the same treatment. He saw one that had strayed from its nest raped in front of its mother. When the chick returned, her mother violently rejected her.

Eventually she wandered off, and tried to join other nests. But it was as though word had spread. She was so violently pecked and chased that Levick felt obliged to kill her to put her out of her pain. Male chicks were no less likely to be targeted.

Illustration: Caroline Villard

Far from being romantic, according to Levick's account, the penguins are necrophiliac, pedophiliac rapists who also present rocks to one another on occasion.

Nearly a century later, in the 1990s, two researchers, Fiona Hunter and Lloyd Davis, went to observe Adelie penguins in their rookeries again. They spent four years watching, and confirmed that the penguins do form monogamous pairs, and do exchange rocks. And they noticed something else entirely. Something that had previously been overlooked.

Hunter and Davies focused on the value of those rocks. They are, in fact, precious — a robust nest is the difference between life and death for chicks and eggs.

Rock theft is rampant, and males will respond as aggressively as they know how — with flipper-bashing and chasing — when another penguin tries to take one.

But sometimes, as a couple sits in their nest, the male drifts into an almost catatonic state of rest and the female slips away. Her destination is a nearby nest-site for bachelors — perhaps Levick’s hooligan males. She will approach a single male, stare sideways at him, and bow — the traditional prelude to courtship. She will then lie prone, which is the male's cue to have sex with, and often impregnate, her.

“Following each copulation,” the researchers observed, “the male dismounted from the female, and she picked up a stone from his nest site and left immediately”. The male did not move a muscle to prevent this. In half the cases, the female returned up to ten times to get more rocks. It was strictly a one-way arrangment. When the affairs occurred at the empty nest of the female, the single male took no rock away with him. The female then returned to her own nest, and presented the rocks to her waiting monogamous partner.

As far as the researchers could tell, this arrangement suited both the female penguin and the single male. The single male paid in rocks for the right to breed, and to have his chicks raised by another male. The female increased the chances of her chicks surviving.

The victim was the kind of romance that penguins have become famous for. The monogamous partners do not appear to know about the arrangement. And some of the single males are tricked. Females perform the rituals of courtship, then take rocks without offering sex. One female took 62 stones from a male in one hour.

And Hunter and Davis realised that some of the single males might not know that the female flirting with them was already in a relationship. They falsely saw her signals as the beginning of a true love.

It is not recorded what they thought once they realised. But it was almost certainly more complex than the myth of the monogamous penguins and their tokens of love. ⸭

This is a free preview of the second story in Bungalow’s first series, Myths and Legends. If you liked it, subscribe here for more.

RAVI SOMAIYA is the founder of Bungalow. You can email him here.