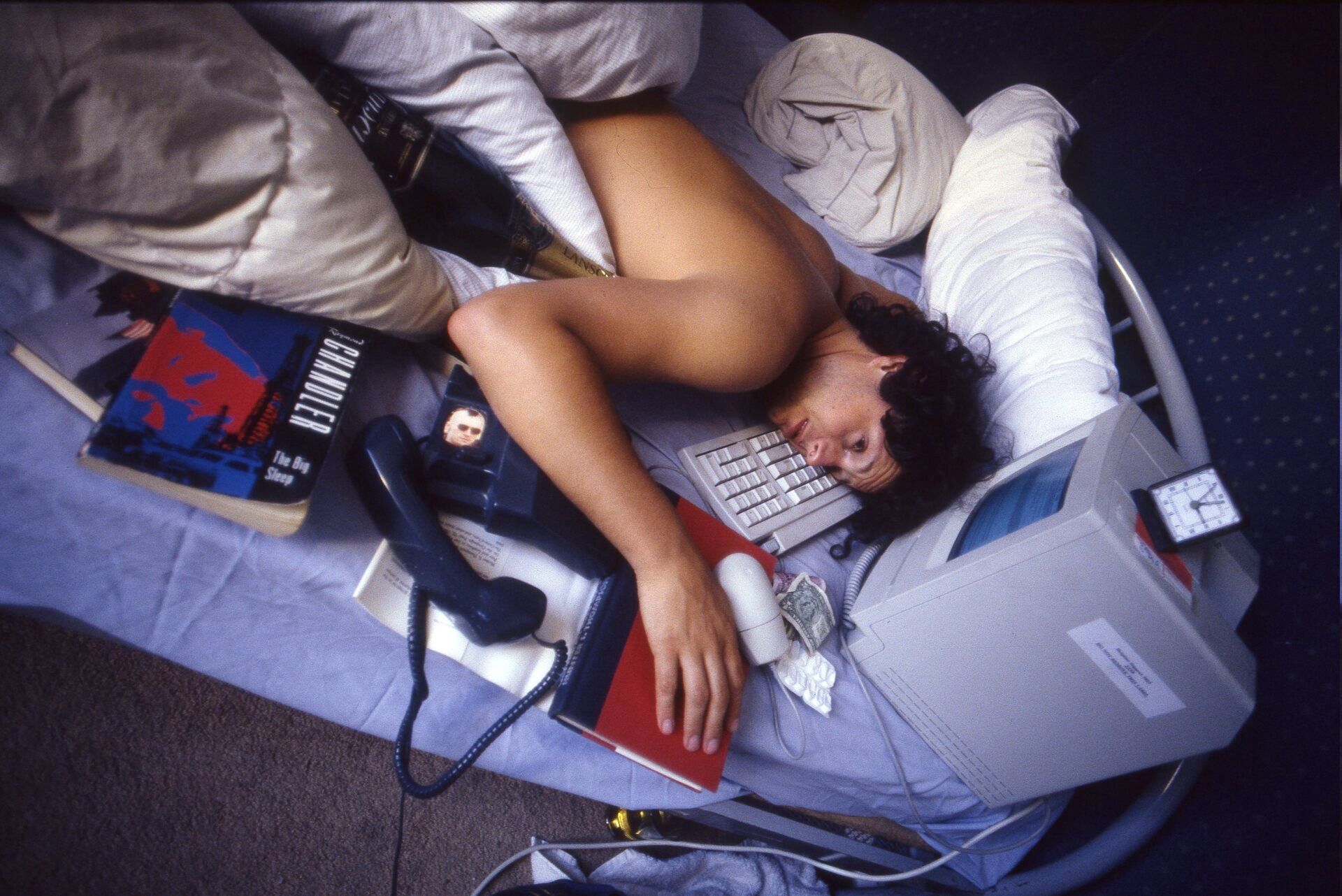

Journalist and editor James Brown in 1997 (Martyn Goodacre/Getty Images)

There is no evidence that Mohammad Farooq, the bomb-maker at the heart of our main story this series, was ever in contact with any actual person to plot an act of terror. For any ideological why, we must turn where he turned — to the influence of his phone. A look through his Instagram feed yields the following:

A matte-black BMW that looks like the Batmobile.

A man wearing a thick gold chain, smoking a cigar on a yacht.

A picture of an explosion.

A man sitting on the front of a holographically-painted Lamborghini in sunglasses.

A picture of a body in a body bag.

A blank-looking influencer lying in a bikini on a stony beach.

It's easy to dismiss the blend of aspiration and titillation and machines and violence that flashes past there, and on the equivalent feeds of many sad boys across the world. It's even easier to blame it for real-world violence, condemn it, and demand censorship. But, argues George Pendle below, there might be another way, with an unlikely inspiration. RS

I WAS A TEENAGER IN 1994, STANDING ON A PLATFORM at London’s Liverpool Street Station, when I opened my first issue of loaded, the prototype for the lad mag.

Features included: “aaaaaaaarrrrrgh!: skydiving for beginners,” “why hotel sex is best,” and a tribute to that celebration of dissipation Withnail and I. Danger, travel, sex, movies, a complete disregard for capital letters, and —thanks to its seven-page Elizabeth Hurley spread — more sex, loaded was teenage boy titillation in its highest form. As the similarly adolescent John Keats once wrote about a very different sort of read, “Then felt I like some watcher of the skies/When a new planet swims into his ken.”

The 1990s were a cultural sweet spot — post-Cold War, pre-War on Terror — a luminous intermission between collapsing and still nascent isms. loaded instinctively knew it. The magazine was, according to its editor James Brown, for “life, liberty, and the pursuit of sex, drink, football and less serious matters."

Practically, it was a hundred TikTok memes in one place. There’s no doubt it objectified women. But it was less cruel than the casual sexism of what had come before (and far less unpleasant than what would follow).

In the UK, the lad mag reached its zenith in 1999. By that time the market had become swamped. Competitors like FHM, Zoo, Nuts, and Maxim each sold hundreds of thousands of copies a month and grew increasingly more unsettling and less amusing. It was at about this time that the idiot lads went from being rebels without a clue to a monoculture.

Loutish hijinks and female ogling started to feel oppressive. When Charlie Brooker and Chris Morris wrote Nathan Barley, a satire of London hipsters, in 2005 they featured a lad mag parody called Sugar Ape, later rebranded (suga) RAPE—which said out loud what many had been thinking.

Over the next decade, as #MeToo grew, academics placed many of the ills of society at the lad mags’ door: Lads’ Mags, Young Men’s Attitudes towards women and acceptance of myths about sexual aggression; More Than a Magazine: Exploring the Links Between Lads' Mags, Rape Myth Acceptance, and Rape Proclivity; Lad Mags and Their Contribution to Rape Culture.

In 2015, loaded printed its final issue (it still exists online, a shadow of its former self).

Yet loaded’s tagline, “For men who know better,” assumed its readers possessed a shred of self-awareness and irony. A decade later we inhabit a darker landscape of incels, groypers, revenge porn, tradwives, sexual choking, Andrew Tate, and the overturning of Roe v Wade. Instead of Liz Hurley posing in her underwear, we have instant access to an infinite quantity of hardcore pornography.

Gone are the useless, funny, drunk lads who actually seemed to like women. In their place a swarm of humorless, protein-obsessed, sober misogynists who preach male supremacism, fear of feminism and unbridled sexual aggression. To quote Tate: “It’s bang out the machete… grip her by the neck… SHUT UP BITCH.”

Academics have again written papers condemning, shaming, and demanding censorship: Sexual Violence in the ‘Manosphere’ — Antifeminist Men’s Rights Discourses on Rape; Your a ugly, whorish, Slut’ — understanding e-bile; Systemic misogyny exposed — Translating rapeglish from the manosphere with a random rape threat generator.

Underlying it all is a doomed idea: that we can cleanse the idiocy and violence from men. A glance at history shows instead that the urges and grotesqueries of young-manhood are eternal. And that these are held off by a thin veneer of civilization. Nothing more than a tacit agreement we make with each other to just... not.

Lad mags, for all their flaws, were part of that veneer—acknowledging lust, redirecting it, domesticating it, leaving it safely visible on the coffee table, rather than hiding it in the private gaze of a phone screen.

As well as being ten years from loaded’s last print issue, it’s also a decade on from the Yale Halloween costume controversy. In October 2015, Erika Christakis, an associate master at Yale University’s Silliman College, responded to an email from the school’s Intercultural Affairs Council that had asked students to be thoughtful about the cultural implications of their Halloween costumes.

“I wonder,” she wrote, “and I am not trying to be provocative: Is there no room anymore for a child or young person to be a little bit obnoxious… a little bit inappropriate or provocative or, yes, offensive?” The answer was no. Christakis was accused of failing to create a safe space for her students and left to dangle in the wind by the university. She resigned from Yale soon after.

But her point remains. Young men need a space where it's okay to be a little obnoxious, a little offensive, a little stupid. If every obnoxious publication or problematic comedian has been shamed into silence, then the only way left to act out is against the very idea of civilization itself. Because, at that point, men don’t know any better. ⸭

GEORGE PENDLE is a senior editor at Air Mail, and the author of Strange Angel, Death: A Life and The Remarkable Millard Fillmore